I am frustrated by the polarized debate about how current and future food needs are to be met sustainably. I am particularly concerned about the extreme position against genetic engineering taken by some self-proclaimed spokespersons for two groups of people: poor and malnourished people, and organic farmers. It is one thing to express one s own opposition to science, or some aspects of science such as molecular biology, genetic engineering within a species, or gene transfer from one species to another. I can live with that even when such opposition is solely an expression of one s ideology, while still ignoring available evidence. Fortunately most of us live in societies where that is possible without serious consequences for oneself. It is quite a different thing to claim to speak on behalf of people who have not asked for such representation and who are likely to be negatively affected by the opposition. It gets even worse when these self-proclaimed spokespersons misrepresent existing evidence.

Ask a developing country farmer who is at risk of losing her crop due to insect attacks or plant disease whether she would like a resistant crop variety. Ask her whether she would like a drought tolerant crop variety. Ask a low-income mother whether she would like to have access to less expensive food and food with higher nutrient content. But they are not being asked. Instead they, or the government officials and policy-makers who are supposed to support them, are being told by certain advocacy groups that such varieties and foods should not be developed and if they have been developed, they should not be made available if they were developed using genetic engineering, even though there are no additional health or environmental risks associated with it.

Genetic engineering is used widely in medical research, where there is little opposition to the use of the technology in solving health problems. Would those opposed to genetic engineering to solve poor people s food and nutrition problems rather die than apply genetically engineered medicine to solve any serious health problem they might develop? They have been asked.

Most of the problems facing farmers and food consumers can be solved without the use of genetically modified biological material, but some cannot and some are solved much better and faster by using genetic engineering. Kids are dying and many more are growing up malnourished because solutions to problems in the food system, including those requiring genetic engineering, are kept away from poor farmers and poor consumers. That is unethical, and those responsible should be held accountable and penalized.

One of the puzzles in the polarized debate is that spokespersons for organic farmers are opposed to genetic engineering. Like most farmers, those producing organically want to make money, but they also want to protect natural resources from mismanagement. Why then, would they be opposed to genetic engineering? Not only are genes organic but genetically engineered crop varieties would help them achieve their production and environmental goals, while reducing the use of pesticides (Yes, pesticides are used in organic farming). Are the spokespersons for organic farmers really driven by ideology or by a desire to promote sustainable food systems that will provide enough food for current and future generations? If it is the latter, then it is time to stop fighting, to ignore the self-proclaimed spokespersons, to take existing evidence seriously, to get together to agree on a set of rules for sustainable food systems that combine the best aspects of organic and conventional production systems, and to implement these rules for the benefit of the people that we all pretend to want to assist. It is time to replace the polarized debate with evidence-based pragmatism.

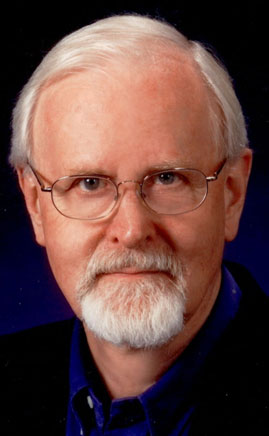

Dr. Per Pinstrup-Andersen is Graduate School Professor at Cornell University. He has served as past Chairman of the Science Council of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), and Past President of the American Agricultural Economics Association (AAEA). He served 10 years as the Director General of the International Food Policy Research Institute, and seven years as department head. He is the 2001 World Food Prize Laureate, and has written extensively about the role of biotechnology in agricultural research and development.